There’s more than one way to mummify a dinosaur, study finds

There’s rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we’re once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2022, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: Why dinosaur “mummies” might not be as rare as scientists believed.

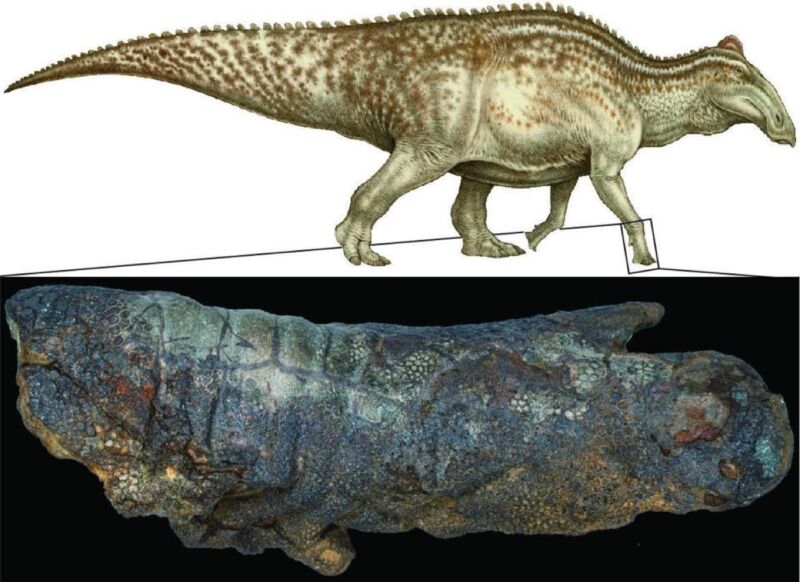

Under specific conditions, dinosaur fossils can include exceptionally well-preserved skin—an occurrence long thought to be rare. But the authors of an October paper published in the journal PLoS ONE suggests that these dinosaur “mummies” might be more common than previously believed, based on their analysis of a mummified duck-billed hadrosaur with well-preserved skin that showed unusual telltale signs of scavenging in the form of bite marks.

In this case, the term “mummy” refers to fossils with well-preserved skin and sometimes other soft tissue. As we’ve reported previously, most fossils are bone, shells, teeth, and other forms of “hard” tissue, but occasionally rare fossils are discovered that preserve soft tissues like skin, muscles, organs, or even the occasional eyeball. This can tell scientists much about aspects of the biology, ecology, and evolution of such ancient organisms that skeletons alone can’t convey.

For instance, last year, researchers created a highly detailed 3D model of a 365 million-year-old ammonite fossil from the Jurassic period by combining advanced imaging techniques, revealing internal muscles that had never been previously observed. Another team of British researchers conducted experiments that involved watching dead sea bass carcasses rot to learn more about how (and why) the soft tissues of internal organs can be selectively preserved in the fossil record.

In the case of dinosaur mummies, there is an ongoing debate over what appears to be a central contradiction. The dino mummies discovered so far show signs of two different mummification processes. One is rapid burial, in which the body is quickly covered, substantially slowing advanced decomposition, and the remains are protected from scavenging. The other common pathway is desiccation, which requires the body to remain exposed to the landscape for a period of time before burial.

The specimen in question is the partial skeleton of Edmontosaurus, a duck-billed hadrosaur, discovered in the Hell Creek Formation of southwestern North Dakota and now part of the North Dakota State Fossil Collection. Dubbed “Dakota,” this mummified dinosaur showed evidence of both rapid burial and desiccation. The remains have been studied with various tools and techniques since 2008. The authors of the PLoS ONE paper also performed CT scans of the mummy, along with an analysis of the grain size of the surrounding sediments in which the fossil was found.

There was evidence of multiple gashes and punctures in the forelimb…

Read More: There’s more than one way to mummify a dinosaur, study finds