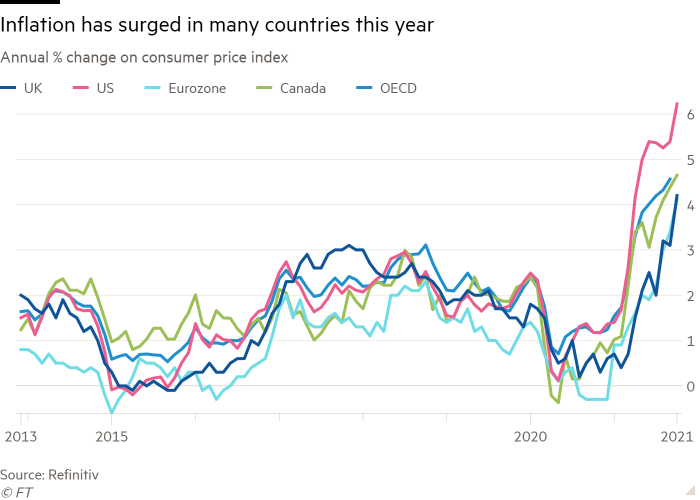

The week central banks got the chills about inflation

This was the week that central banks around the world changed gears and got serious about inflation.

Gone was talk from the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank or Bank of England that rapidly rising prices were temporary, transitory or transient. Instead, they began to worry about high inflation being “persistent”.

The ECB and Fed sharply scaled back their programmes of asset purchases. Central banks in two rich economies, the UK and Norway, raised interest rates. Nine emerging economy central banks, ranging from Chile to Russia, also pushed rates higher. Even the Bank of Japan, more often concerned with deflation, dialled back its coronavirus crisis monetary support.

Rarely has there been such a clear shift across the global economy towards a more hawkish outlook on inflation. Ajay Rajadhyaksha, head of macro research at Barclays, said: “Central banks are clearly pivoting to a tightening regime far more quickly than appeared likely just a few months ago”.

Francesco Pesole, foreign exchange strategist at ING, said the most important new message this week was “the centrality of inflation in the policy discussion”.

As well as putting inflation at the centre of their thinking, officials in charge of monetary policy downgraded the importance they attached to coronavirus and its effects on economic activity. Statements from the Fed, ECB and BoE all highlighted the uncertainty surrounding the Omicron variant. But none thought it would be pivotal to policy in coming months.

In the US, Fed chair Jay Powell said Omicron “doesn’t really have much to do with” its plan to accelerate the removal of pandemic-era monetary stimulus.

Christine Lagarde, ECB president, stressed that “our economies have become more resilient, stronger and are more capable of adjusting wave after wave after wave, and variant after variant”. As for the UK, BoE governor Andrew Bailey said it was unclear if Omicron would add to or lessen inflation pressure “and that’s a very important factor for us”.

There was no sign these responses were co-ordinated. Yet the consistency of their message has raised concerns among some economists that leading central banks may have forgotten how corrosive coronavirus waves can be.

“The central bankers who have taken this hawkish, or less dovish in the ECB’s case, tilt were never imagining . . . in October and November that there would be this bolt from the blue with Omicron,” said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics. “I’m surprised that there is not a little bit more willingness to accept that things actually could be quite bad for a while.”

The underlying reason driving the rise in inflation is global demand exceeding the world’s capacity to supply goods and services. Yet while leading central banks acknowledged the problem, how they chose to address it varied.

The Fed’s rapid withdrawal of quantitative easing, and the signal it will raise interest rates three times next year to leave them at between 0.75 and 1 per cent, was well telegraphed. Yet the view among some economists was this was too little too late — given that US inflation, at almost 7 per cent, is…

Read More: The week central banks got the chills about inflation