The U.S. delves into the pain inflicted on Indigenous communities through

Ground-penetrating radar this year revealed hundreds of unmarked graves at former residential schools in Canada.

The harrowing discovery — remnants of a government policy that sought to eradicate Indigenous cultures by separating an estimated 150,000 children from their families from the 19th century through the 1990s — prompted reaction from religious leaders and public officials worldwide.

In the U.S., Interior Secretary Deb Haaland wept when she saw the headlines from Canada. She is a member of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, and her maternal grandparents were among the children subject to a similar policy on this side of the border. The Interior Department, which she now runs, oversaw hundreds of boarding schools for more than a century.

Native American leaders and community members have repeatedly called on the U.S. government to take accountability for these family separations, which historians describe as part of efforts to break up tribal control of territory. In late June, Haaland, who became secretary this year as part of the Biden administration, instructed the department to prepare a report on the boarding school policy and its ramifications by April 2022.

“Survivors of the traumas of boarding school policies carried their memories into adulthood as they became the aunts and uncles, parents, and grandparents to subsequent generations,” Haaland wrote in a memo on the initiative. “The loss of those who did not return left an enduring need in their families for answers that, in many cases, were never provided.”

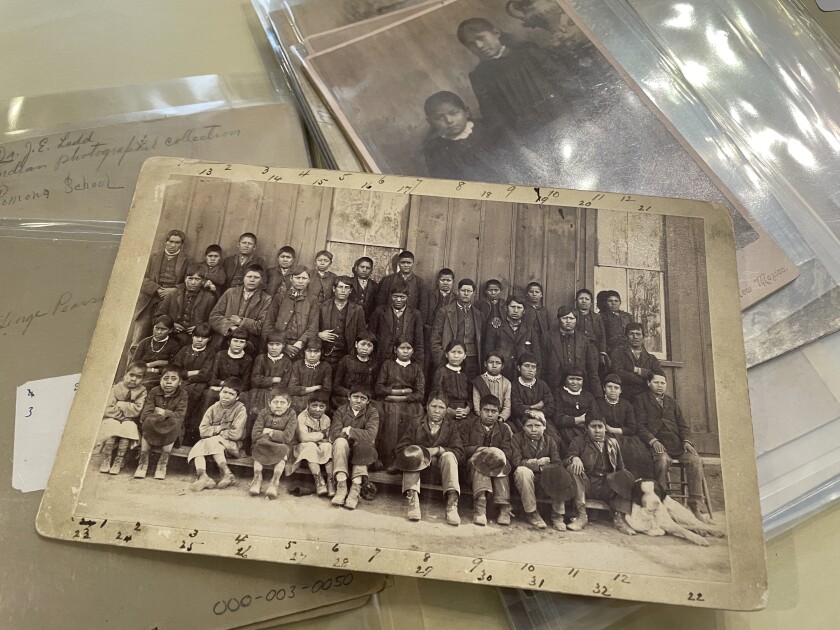

A photograph archived at the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico shows a group of Indigenous students who attended the Ramona Industrial School in Santa Fe. The late 19th century image is among many in the Horatio Oliver Ladd Photograph Collection related to the boarding school.

(Susan Montoya Bryan / Associated Press)

Haaland’s initiative was commended by the National Congress of American Indians, which represents 574 federally recognized tribal nations. However, the organization maintains that a truth commission — in the style of those in many countries that have sought to atone for their past — is needed to move forward, one that includes support for survivors and their descendants.

Here are more details about the issue:

What were the boarding schools in the U.S. like, and what did they aim to achieve?

According to historians, from the 19th century through the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous families were forced to send their children to boarding schools run by the federal government or religious groups. For those on reservations, coercion ranged from having their food rations denied to being imprisoned for refusing to give up their children.

The precise number of campuses remains unknown, said Denise Lajimodiere, a historian, educator and founding member of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, a nonprofit group formed in 2012 to raise awareness about the policy.

But after years of work — including reviews of university archives, government offices,…

Read More: The U.S. delves into the pain inflicted on Indigenous communities through